In his previous post, Craig Morris began his summary of the 1985 book entitled (in German) The Energiewende is possible. Today, he sheds light on how the trend towards large power plants created unnecessary costs in the process – although more efficient distributed cogeneration was an alternative.

German utilities consciously overbuilt conventional capacity to bring down industrial power prices, shifting the cost burden onto consumers. (Photo by Stodtmeister, CC BY 3.0)

The authors of the 1985 Energiewende book say that regulators of power monopolies were not as savvy as the utilities they monitored. The regulators focused on prices but not on whether particular projects needed to be built. Power companies managed to convince the regulators that everything proposed was needed to prevent blackouts. The threats of blackouts were not properly questioned.

Because the government approved power prices, the utilities had to make a profit; it is, quite reasonably, against German law for the government to force private enterprises to do business at a loss. The 1980 German Electricity Tariff Regulation specified that “the state must ensure a reasonable profit, without which the security of energy supply cannot be ensured.” The authors conclude that “it was impossible for investments to lead to losses.”

But the regulation scheme described above essentially incentivizes overbuilding. If a utility wants to increase its profits, it needs to increase revenue – the profit margin is more or less a percentage set by the government and cannot change much.

During the overbuilding, the focus on large power plants also partly resulted from the structure of cross subsidies. Large industry could theoretically set up their own small plants, so utilities had to underbid those options. Large plants have high upfront capital costs with relatively low operational costs. The high capital costs are the thing utilities can pass on at a regulated profit margin to defenseless households, whereas the low operational costs allow utilities to sell at cutthroat rates to large industry customers. Unlike industry, households could not produce their own power cheaply in the 1980s, so costs were passed on to them. Today, small power consumer still cross-subsidize large ones. All of these factors came together to make a focus on ever larger power plants seem obvious from every angle – except efficiency (see previous post).

My favorite part of the 1985 Energiewende book comes when the authors investigate RWE’s announcement of what the firm proudly called the “largest and most complex environmental protection program ever undertaken by a single company.” The price tag was 9 billion deutsche marks. The authors were not impressed: “Essentially, the firm is saying that it will charge an additional 9 billion marks to its customers, and in return it will also receive even larger profits because the guaranteed profit margin is a percentage of overall revenue. And the company even expects applause.”

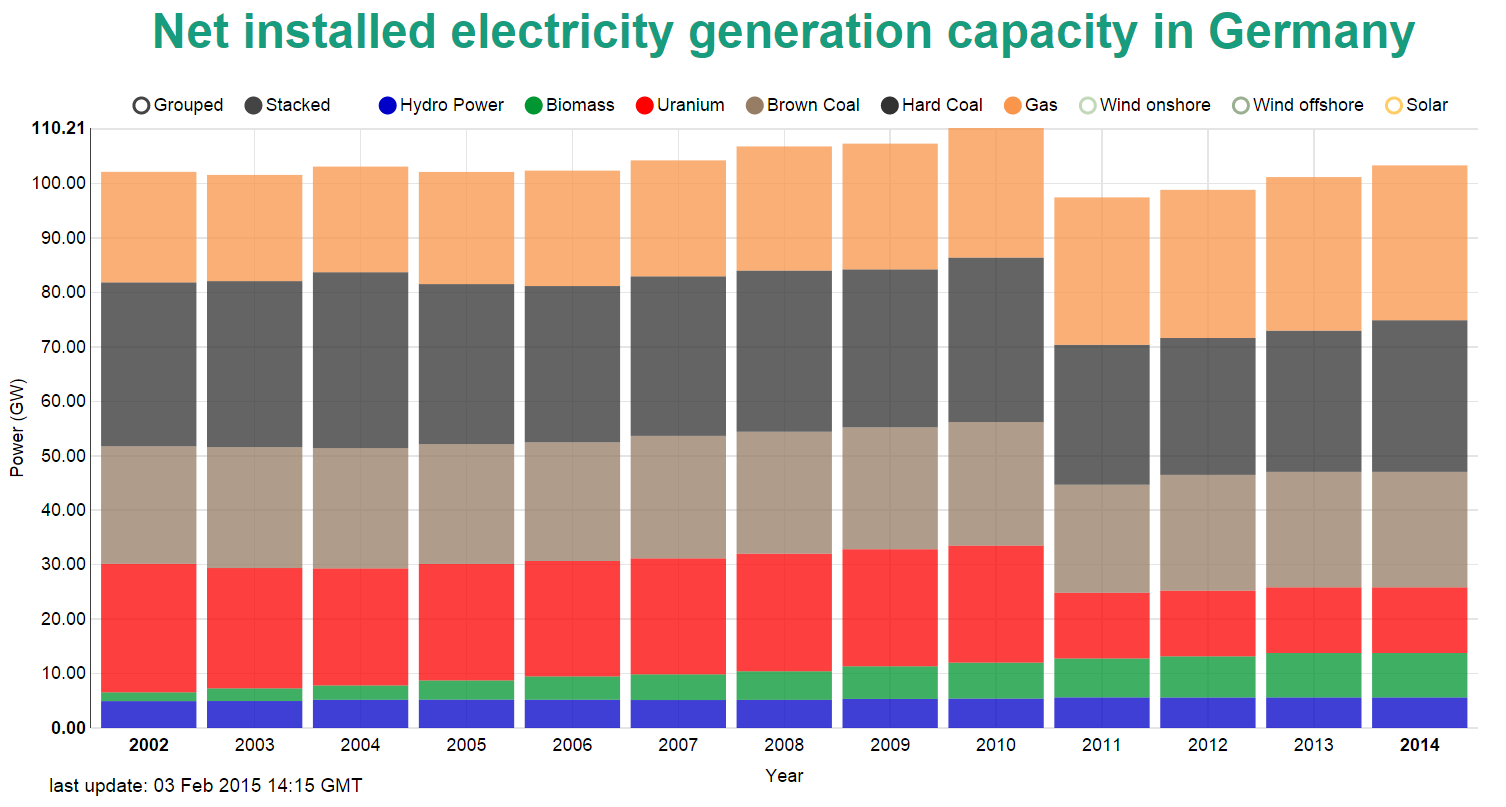

Although German power demand peaks at only around 80 GW, the country reliably had more than 100 GW of dispatchable capacity (excluding solar and wind) until the nuclear phaseout of 2011 – a reserve margin of around 25 percent. The additional plants added since 2011 bring the country back up to that level. Grid experts estimate that closer to 10-15 percent backup reserve capacity is needed. From 1973 to 1982, the authors found that there was roughly a 40 percent reserve. Source: Fraunhofer ISE (energy-charts.de)

“High-voltage power lines not needed for energy transition”

The large power plants had knock-on effects. The authors cite the city of Osnabrück (population: 150,000) as an example of how even midsize municipalities were able to make do with a 20 kV grid. But the large power plants required 110 kV and eventually 380 kV lines. Today, the expansion of these high-voltage lines is a tremendous bone of contention in Germany’s energy transition. The historic irony is that all of these high-voltage lines that the Energiewende allegedly now needs were actually built for the large central power plants that the energy transition needs to get rid of now.

The industry customers hooked up to those lines covered only half of the cost for the 380 kV lines – and paid no other grid costs. The rest was passed on to the defenseless small consumers.

Today, firms that consume enough electricity (the ones that thus need the grid the most) are exempt from the grid fee. A German court even ruled in 2013 that the practice was unconstitutional (report in German), but that does not seem to have changed anything, for this report from October 14 2014 (in German) says the number of exempt firms now exceeds 4,000 – so it is rising. We have also written extensively about industry exemptions from the renewable energy surcharge. As the Energiewende book from 1985 shows, this policy has a tradition.

Utilities claim that the focus of energy policy is on reliability and affordability. “Affordability” was obviously, though not explicitly, defined in terms of large consumers, not households. In terms of reliability, the authors convincingly argue that large power plants actually endanger supply security. A major outage occurred on 17 February 1985 in France, for instance (while the book was being written), when 6,200 MW failed at once. We have also discussed in this blog the difference between fluctuating renewables and intermittent conventional power – when large conventional plants fail (and they do), filling that gap quickly poses a tremendous challenge. Towards increasing supply reliability, a larger number of smaller plants would make much more sense.

Overbloated backup reserve needed for large conventional plants

The need for large backup plants further increased surplus capacity. Recently, I wrote about how the German government wants to continue to hold power plant owners responsible for plants that fail. The idea is that, when a 600 MW coal plant (or a 1,200 MW nuclear plant) goes down unexpectedly, that plant operator must fill the gap. When all the plants are large, so are the backup plants. (Note that these redundant power plants were originally not needed to back up renewables, but other conventional plants.)

In 2011, when Germany suddenly shut down eight nuclear plants within a week, the world realized how much excess capacity the country actually had – the immediate closure of around a tenth of installed conventional capacity caused no problems at all. On the contrary, the country reached record power exports in 2012, 2013, and 2014. And again, there is a tradition to this excess capacity.

In my next and last post on this book, I investigate the remedies the authors proposed.

The series reviews the 1985 follow-up book on the Energiewende study from 1980. That book was also reviewed here in 2013:

- Looking back at the Energiewende 1980 – 55 Percent Coal?

- Looking back at the Energiewende 1980 – Nuclear Cannot be Efficient

- Looking back at the Energiewende 1980 – Time for a Coal Phaseout

- “Efficiency lacks a loud lobby”: An interview with Florentin Krause

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.