A study published by German university researchers for German engineering firm Siemens finds that the renewable power installations built since Fukushima have not affected the retail rate, but they have brought down wholesale rates considerably. Energy-intensive industry has benefited the most. But Craig Morris says there is something for the nuclear camp to criticize.

Without renewables, the German phase-out of nuclear that (re-)started in 2011 would have been much more costly, especially for industrial consumers. (Photo by Doblonaut, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The study – available as a PDF in German – comes to a number of pleasant conclusions for proponents of renewables. For instance, the researchers found that Germany might have suffered blackouts in 2013 if less renewable capacity had been added. On 269 hours that year, Germany would have needed to resort to its strategic reserve and begin importing electricity to prevent a blackout. In reality, Germany only used its winter reserve once in 2013, and the country posted a record level of net power exports that year. In 2014, the winter reserve was only used on December 20 and 22.

What’s more, the cost impact of renewables in Germany (the renewable energy surcharge or EEG-Umlage) amounted to 20.4 billion euros, but the researchers found that this investment offset some 31.6 billion euros in conventional electricity – a whopping 50 percent return approximately.

The cost savings have been passed on entirely to industry. The researchers find that the retail rate would practically be the same today, whereas wholesale rates – which have a much greater impact on industry prices – would be more than twice as high. (I explain how the renewable energy surcharge works here.)

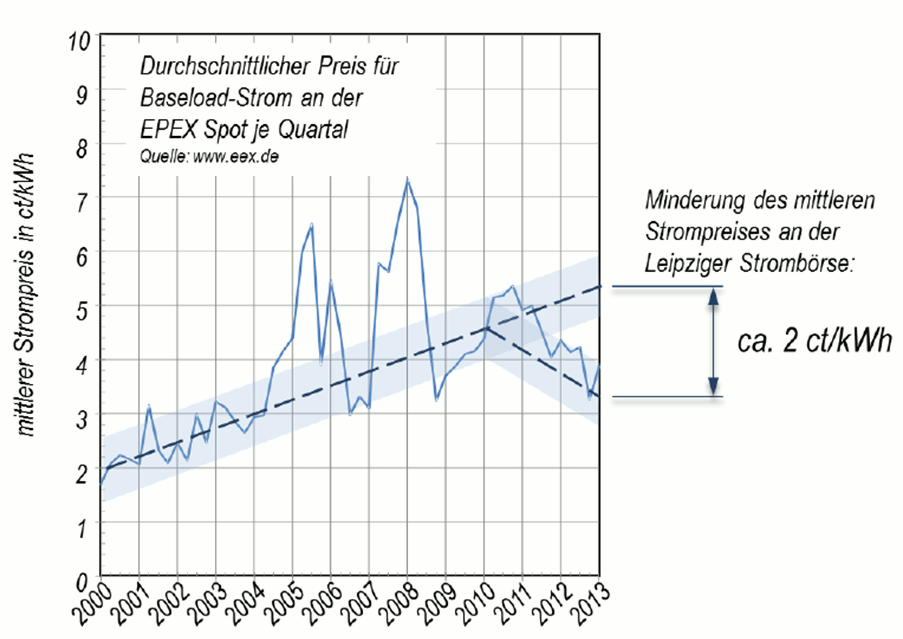

This finding is nothing new or surprising. This month, for instance, the Becquerel Institute conducted a similar study focusing solely on how PV has brought down wholesale prices across numerous countries in Europe (PDF). Over the past year or so, I have been pointing out that energy-intensive industry – aluminum, paper mills, steel, etc. – is the big winner in the Energiewende. I did so based on news about corporate decisions. This university paper adds a price estimate to the discussion – without renewables, the price on the exchange would have averaged 9.07 cents in 2013, rather than 3.78 cents. The following chart shows an estimate of the impact since 2011.

This is where the study begins to fall apart for me. In the paragraph above, we read that renewables have reduced wholesale rates by more than five cents, but the chart shows that the effect has been two cents since 2011. It all depends on your assumptions. If we take out a lot of renewables, we end up with a greater differential.

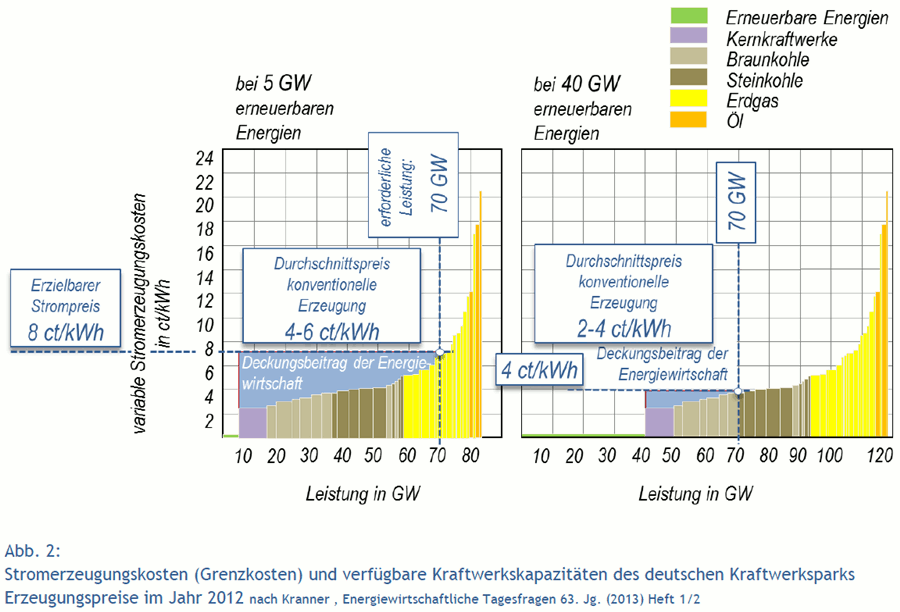

A depiction of the “merit order”. Here, we see how prices increase (Y-axis on the left rising up) as demand increases (x-axis from left to right on the bottom). At a given level of consumption – here, 70 GW – the amount of renewable power generated greatly impacts the marginal price. On the left, we see that around 5 GW of renewable electricity means that the cost of power rises to around eight cents per kilowatt-hour. On the right, 40 GW of renewable power (an additional 30 GW) reduces that price to around four cents. Note that the GW figures do not represent installed capacity, but actual generation. Germany currently has around 76 GW of wind and solar capacity combined, but those two sources collectively generate around 20 GW on average (because the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow all the time).

To reach these conclusions, the paper makes unrealistic assumptions. For instance, a wholesale price of nine cents would incentivize a lot of new plant construction. Yet, the paper assumes that nothing would have been added on. Likewise, supporters of nuclear will immediately wonder why the paper does not calculate the cost impact of a counter-scenario, with nuclear not having been shut down in 2011. The authors would probably (and correctly) argue that such a scenario is completely unrealistic in Germany – but then again, so is the assumption investigated (no additional renewable or fossil generation capacity). Indeed, the nuclear phaseout and the transition to renewables are historically inseparable.

Indeed, the paper is just as interesting for its assumptions as it is for its findings. More than anything else, it shows what constitutes acceptable discourse in Germany today. Clearly, it is taboo to talk about saving money by keeping nuclear plants open. The paper instead makes headlines with its main finding: renewables have made electricity cheaper and power supply more reliable. That’s what everyone wants to hear, and now that the authors have everyone’s attention, they can get to their real message: the nuclear phaseout will make “additional generation capacity, especially to cover peak demand, indispensable – such as gas turbines and storage technologies.” The paper estimates that the shutdown of the last six nuclear plants in Germany in 2021 and the 2022 will increase wholesale prices in those two years alone by nearly 2 cents to 4.5 cents, depending on renewable energy growth. (The need for storage in 2023 is by no means a foregone conclusion, incidentally.)

I am not the only one saying this paper is unrealistic. My German colleague Benjamin Reuter says that the study investigates a “worst-case scenario” (in German) and adds that, in addition to the possible capacity adjustments mentioned above, efficiency is not investigated either. The paper acts as though higher prices would not be a signal for lower consumption.

Nonetheless, it is a considerable improvement upon previous Siemens statements and publications on the Energiewende. In January 2012, a Siemens executive put the cost of the nuclear phaseout at 1.7 trillion euros, equivalent to around 1.65 euros per kilowatt-hour – more than five times the current retail level and easily several times more than new solar power stored as hydrogen (or P2G, the most expensive option) would cost today. In 2013, Siemens put out an official publication on how the cost of the Energiewende (a hot topic at the time) could be kept in check, but a closer look revealed that it was a sales brochure recommending practically everything the company sells and disparaging what it doesn’t sell (for instance, it said solar was too expensive).

One of the authors of the study works on next-generation biomass; the other, on P2G. And of course Siemens is a big player in the energy sector (but not necessarily in the energy transition). The best news about this study is not its findings, though they will no doubt be widely circulated. Rather, it is a sign that Siemens has moved from unrealistic criticism of the Energiewende to unrealistic cheerleading for it. Two cheers for Siemens!

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.