In August, France announced the first steps of its Energiewende, called transition énergétique. Mat Hope compares France’s latest efforts to the efficiency and renewable policies that are already in place in the UK and Germany.

One continent, numerous approaches: Three different energy transition paths are emerging in the UK, France and Germany.

This article was first published on The Carbon Brief.

France has announced it will undertake an ambitious energy sector transformation that will see the country cut greenhouse gas emissions 40 per cent by 2030. France joins neighbours Germany and the UK, who both have their own legislation to cut energy sector emissions. If the plans come off, they will leave the EU’s three biggest economies with radically different power systems to those they’re operating today.

Such transformations aren’t technoligically straightforward, and getting the public to back such ambitious schemes hasn’t always been easy.

Here’s a look at the three countries’ respective plans, and the challenges they’re likely to face.

Transition énergétique

France, Germany and the UK all have ambitious policy programmes to cut energy sector emissions.

The UK has had legally binding emissions reduction goals since 2008, and passed a law late last year outlining a range of new schemes designed to achieve them. Germany began implementing sweeping reforms to decarbonise its energy sector in 2010, known as the Energiewende. France has just followed suit, passing a law in August that was described by France’s environment minister, Ségolène Royal, as “the most advanced legislation in the European Union”.

The transition énergétique pour la croissance verte puts France “in the same ballpark as Germany and the UK” in terms of policy ambition, green business organisation The Climate Group said in a press release.

All three programmes depend on public acceptance, to an extent. Experience in Germany and the UK suggests this will be particularly important in two areas: household energy efficiency and renewable energy generation.

Energy efficiency

All three countries intend to meet their emissions goals in part by reducing energy consumption. Germany intends to cut consumption 50 per cent by 2050, compared to 2008 levels. France intends to cut energy use by 50 per cent compared to 2012 levels. The UK’s emissions goals imply cutting demand by between 31 and 54 per cent on 2007 levels.

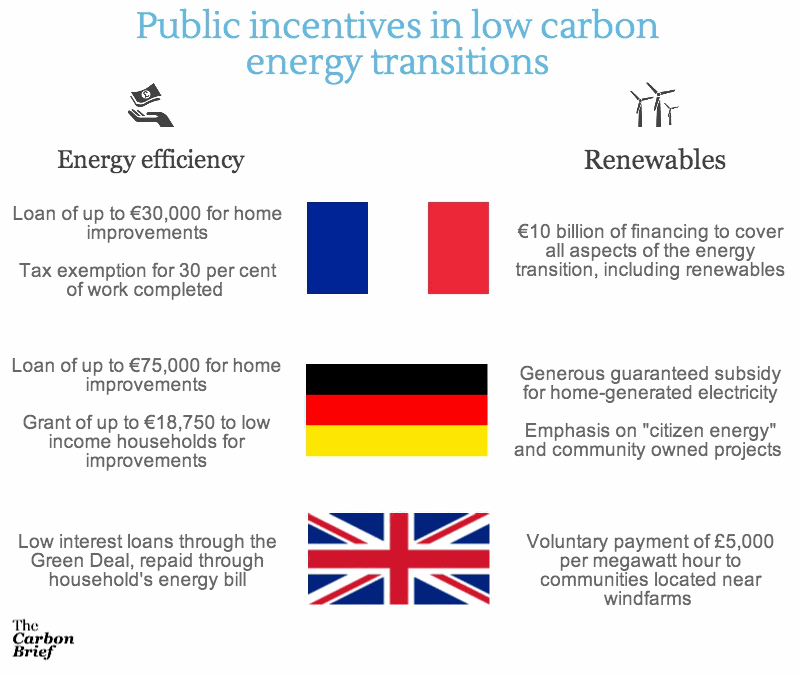

So what kind of incentives are on offer for those taking up energy efficiency measures?

Germany and the UK both offer incentives for people to replace make home improvements such as replacing their old and inefficient boilers, and installing insulation. In Germany, state-backed bank KfW offers grants of up to €18,750 and loans of up to €75,000 for home improvements. The UK government started offering a similar deal in 2012, the Green Deal.

But public take-up of the low interest loans was slow. So in June, the the government decided to offer cashback for improvements worth up to £7,600. The offer was retracted six weeks later after a flurry of applications exhausted the £120 million fund. The UK government also cut another scheme – the energy companies obligation (ECO) – last year, after pledging to reduce the so-called green levies households paid on their bills.

In July, industry group the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE) put Germany top of its global energy efficiency rankings. The UK government’s reforms saw the country fall from first to sixth in the same league table.

France hopes to cut energy consumption in a similar way to Germany.

In 2009, France launched a scheme requiring banks to offer zero interest loans for energy efficiency home improvements worth up to €30,000 (known as ECO-ptz). France also has an energy company obligation scheme, similar to the UK’s, that requires companies to help customers reduce consumption. France’s government hopes continuing the schemes while implementing stringent building codes will help it hit its energy efficiency goal.

Renewable energy

If renewables are going to provide 40 per cent of France’s electricity in 2030 – as the new law requires – the government is going to have to ask communities to host a range of renewable energy developments. That likely means implementing some sort of incentive scheme.

Both Germany and the UK offer the public some sort of sweetener to get them to back a renewables surge. So far, Germany has been more successful in stimulating public suppport for the transition than the UK.

Germany’s Energiewende emphasises the development of citizen owned energy projects, or Bürgerenergie. In 2013, over half of Germany’s renewable energy was owned by citizens.

That’s because the government guarantees generous prices for home-generated energy – mainly from rooftop solar panels – that’s then sold back to the grid. It’s also down to the growth of cooperatives, where communities pool their resources to construct larger renewable energy projects to provide power for their neighbourhood.

Such investments mean consumers see long-term returns on their investment, and helps secure public support for the Energiewende.

The UK takes a different approach. Large energy generators still dominate the UK market, owning almost all of the UK’s generating capacity. When they want to build a new windfarm, they offer communities £5,000 per megawatt hour of installed capacity, in line with government guidelines.

But such compensation doesn’t give communities as much of a stake in renewables as they experience in Germany, meaning opposition is still fairly commonplace. As Geoff Wood, an energy researcher at the University of Dundee, previously told Carbon Brief:

“Looking at the areas of large-scale renewable deployment – subsidies, the complexity of the system, investment risk, policy risk, planning and supply chains – the thread running through it is the sheer lack of proper public participation”.

That can lead to more local opposition to renewable energy projects, he told us.

France wants to emanate Germany’s success, but looks set to try and do so using a more British-looking policy model.

The French government has allocated €10 billion to finance the first three years of the energy transformation. Currently, there’s little indication the French government will spend that money incentivising community energy generation.

Pierre Cannet, head of WWF France’s climate change and energy programme, tells Carbon Brief that France’s approach is “very different from Germany”. That doesn’t mean the public will be sidelined forever, but “democratisation or other ways to involve to involve the public in the energy transition is yet to be built”, he says.

So while France’s government is pitching its energy transformation at the same level as Germany’s, its policy approach appears to have as much – if not more – in common with the UK.

The details are due to be hammered out in France’s parliament over the coming months. Once the parliamentarians are done, we’ll have a better idea of what lessons France has learned from its nearest neighbours.

This article by Mat Hope (@matjhope) was first published at The Carbon Brief and is reposted with permission.