In 2011, Germany switched off 8 of its 17 nuclear plants. Since then, the country has made headlines not only for its campaign to reduce energy consumption and ramp up renewables – the “Energiewende” – but also for increasing production of coal power in 2013. So is Germany’s energy transition in reality more a switch to coal than to renewables? And is renewable electricity incapable of replacing the country’s nuclear power? Craig Morris investigates in part one of a three-part series.

Lignite-fired Boxberg Power Station in 2009 with the newly commissioned unit under construction on the left – exception or part of a bigger coal renaissance in Germany? (Photo by Frank Vincentz, CC BY-SA 3.0)

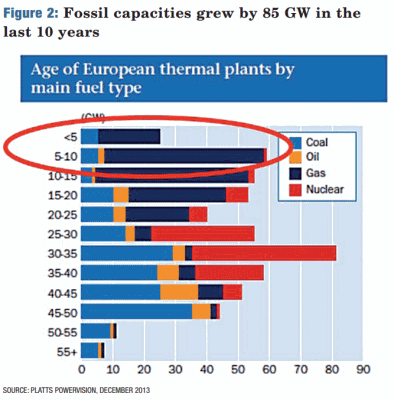

In November 2013, Bloomberg reported that Germany would complete 10 new hard-coal power plants with a cumulative capacity of eight gigawatts within two years. The figures come from Germany’s Network Agency, which now publishes its own list (only available in German). Peak power demand in Germany comes in at around 80 GW, so eight new GW of coal is quite a bit – 10 percent of total peak demand.

German environmentalists are clearly concerned. BUND, the German chapter of Friends of the Earth, publishes its own overview (PDF in German) of coal plant plans. The version from April 2013 had nine new hard-coal plants under construction or in planning along with an additional two lignite plants.

Not only is more capacity being built, but more coal power is also being generated. In 2013, production of electricity from brown coal in Germany rose only slightly by roughly 0.7 percent – but that level was the highest since 1990 and eight percent higher than in 2011. Likewise, power generated from hard coal grew by 10 percent from 2011-2013.

As Bloomberg points out, the new 725 MW hard-coal plant was the first completed in Germany since 2005, but it wasn’t the only new one last year. In 2013, a 746 MW hard-coal plant was also finished. And in 2012, two lignite plants were completed: the relatively small 640 MW units at Boxberg, and the giant 2100 MW Neurath plant.

Source: http://www.greenpeace.org/austria/Global/austria/dokumente/Reports/klima_Locked_in_the_past_2014.pdf

When then-German Environmental Minister Peter Altmaier attended the opening of Neurath, he pointed out that the modern plant was replacing a number of older, less efficient coal plants. But even if we subtract the 3,645 MW of lignite and hard coal retired since 2011, Germany still added 566 MW of generation capacity.

When we consider that Germany added almost no coal capacity in the previous decade, we must ask ourselves why there was the sudden boom in hard coal. Specifically, is it a result of Germany’s nuclear phaseout of 2002?

Conventional wisdom: decommission capacity has to be replaced

In 2000, the government of Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder signed an agreement with the country’s utilities to phase out nuclear. Each plant was given the equivalent of 32 years of terawatt-hours in line with its capacity. The firms were to shut down each plant when its number of TWh had been exhausted, but they were also able to shut down a plant ahead of schedule and transfer the remaining TWh to another nuclear plant.

In 2002, the agreement became law, and in 2003 the first nuclear plant was shut down: the 31-year-old Stade facility, with a capacity of 672 MW (its remaining TWh were passed on to another plant). In 2005, the next plant was shut down – the 36-year-old 357 MW plant in Obrigheim. In total, just over a gigawatt of nuclear generation capacity was thus switched off under the nuclear phaseout agreement of 2000.

In 2005, the Social Democrat/Green coalition lost the elections, and the new coalition consisted of the Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Social Democrats (SPD). In 2009, the SPD was voted out of the coalition and replaced by the libertarian Free Democrats (FDP). From 2005 to 2009, nuclear plant operators – hopeful that a CDU/FDP coalition would win the 2009 elections and throw out the nuclear phaseout – made sure that no other plant used up its allocation of terawatt-hours. The next plant to go after 2005 would have been Biblis A around 2009-2010, depending on how long it took for the plant to generate its allotted kilowatt-hours. Biblis B was to go roughly a year later. When it was discovered in mid-October 2006 that new dowels added to make the plants more earthquake-resistant had been incorrectly installed, Biblis B remained off-line until December 2007 – Biblis A, until February 2008.

An attempt to have kilowatt-hours transferred from a younger plant to Biblis A was quashed the same month that it went online, but any new government taking office at the end of 2009 would then clearly have time to extend nuclear plant commissions before these two plants used up their power allotments. At the end of 2010, Chancellor Merkel extended nuclear plant commissions by 8-14 years – only a few months before the accident in Fukushima.

If we look at the investment activity that began in 2005, we might suspect that firms saw a need to replace this decommissioned nuclear generation capacity. And indeed, it takes around five or six years in a democracy for a coal plant to be built. Planning for the coal plants that have been completed in the past couple of years generally began between 2005-2007 – in Boxberg (completed in 2012), for instance, planning began in 2006.

No doubt the investment surge reflected an expectation among power providers that new capacity needed to be built. Sigmar Gabriel, the current Industry Minister, was Environmental Minister from 2005-2009. In 2009, he made such statements as: “Those who protest against coal power will end up with nuclear” and “we need 8 to 12 new coal plants if we want a nuclear phaseout.” His position has not changed. In 2011, he reiterated his stance by saying, “We shouldn’t act like we can phase out nuclear, coal, and gas at the same time,” and added, “We need the 8 to 10 power plants currently being built.” In 2014, he said the calls for a simultaneous nuclear and coal phaseout were “irresponsible.”

He is not alone in his opinion. Germany’s current Environmental Minister Barbara Hendricks was recently quoted saying that coal power is “important to the country’s economic security and should not be subject to extreme negativity.” She added that, “We must not demonize coal.”

In my next post, we learn whether these expectations were correct.

Craig Morris (@PPchef) is the lead author of German Energy Transition. He directs Petite Planète and writes every workday for Renewables International.