A few weeks ago, German Environmental Minister Peter Altmaier (Christian Democratic Union – CDU) said he planned to redesign German energy policy so that the renewables surcharge passed on to ratepayers would not rise any further. Altmaier provided details last week, just days after the Greens produced their own counter-proposal. Craig Morris takes a look at this proposal.

In a PDF (in German), the German Greens have published their own proposals for a reform of German renewable energy policy. While they agree that “a lot needs to be changed,” the Greens say they are “focusing on what can be done before the upcoming parliamentary elections.”

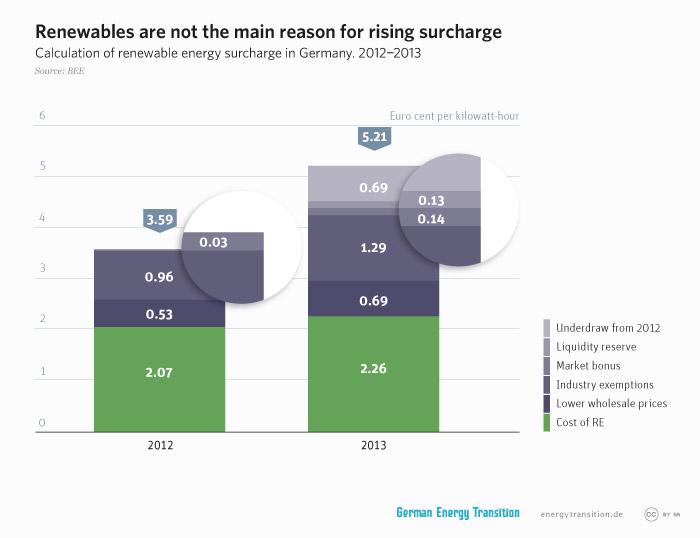

What is the issue? Basically, German the cost of feed-in tariffs is passed on to all ratepayers – but there are some loopholes and exceptions. As a result, the actual cost of renewable electricity only rose from 2.07 to 2.26 cents per kilowatt-hour from 2012 to 2013, but the overall surcharge increase from 3.59 to 5.21 cents.

Obviously, most of the surcharge is now unrelated to the actual cost of renewable power. The main cost drivers are various industry exemptions and the falling price of wholesale power.

The industry exemptions have been there all along – since the Renewable Energy Act was first adopted in 2000. The thinking is that some energy-intensive industries – such as aluminum, where energy costs make up more than half of production costs – face international competition. Having such firms pay higher power prices would make Germany less attractive for such industries; hence, the exemption.

The problem is that the scope of these exemptions has roughly tripled over the past few years and now includes firms that cannot possibly leave the country, such as public transit systems. And as this video by Deutsche Welle shows, the firms that just barely fail to make the cut have to pay more than their fair share of the burden; the surcharge is increasingly spread across a smaller number of shoulders.

The second problem seems paradoxical: wholesale power prices fell by around 20 percent over the past year, thereby increasing the renewables surcharge. But this outcome was foreseeable; indeed, it is by design. The cost of electricity on the exchange is deducted from the feed-in tariffs paid for renewable power. Because renewables are offsetting peak and, increasingly, medium load power, wholesale electricity is getting cheaper – so less is being deducted from the surcharge. As the Greens’ position paper puts it, “Even if nothing is invested in renewables in a given year, the surcharge could nonetheless increase” if wholesale prices dip even further.

What do the Greens propose?

First, the Greens point out that total expenses for electricity still only make up 2.5 percent of nominal gross domestic product, the same as in 1991. The problem is, the Greens argue, that the burden is not being shared equally.

The Green position paper calls for a number of things currently called into question to be retained:

- renewable power must continue to have priority access on the grid, meaning that all renewable power generated must be paid for even if conventional power plants have to ramp down

-

different feed-in tariffs should be paid for different technologies and system sizes; this stipulation is a counterargument to the proposal that all kinds of renewable power should be paid a single price based on what the grid needs at a given moment – in which case wind power would generally be the only thing built

-

the surcharge should continue to be immediately passed on to ratepayers and not taxpayers; while ratepayers and taxpayers are often the same, the problem with having the surcharge as a governmental budget item is that most countries currently run a budget deficit, so the costs are unfairly passed on to future generations; furthermore, budget items have proven unreliable and unpredictable as sources of funding for renewables, both in Germany and elsewhere

The Greens would like to change the following:

- firms would have to consume at least 10 gigawatt-hours per year to be exempt from the surcharge, as was the rule up to 2009, when the limit was lowered to one gigawatt-hour

-

firms filing for exemption would have to demonstrate that they actually face international competition

-

the reduced surcharge for such firms (currently 0.05 cents instead of 5.2 cents) should be increased as these firms are already benefiting from lower wholesale power prices

-

renewable power consumed directly (i.e., not sold to the grid) should also have to contribute to the surcharge

-

wind power on shore is still the cheapest source of renewable electricity and should be further promoted

-

the “market bonus” provided as an option to feed-in tariffs has proven to be more expensive than FITs and should be replaced by a less expensive “green power privilege”

Those are just the changes the Greens want to make to the Renewable Energy Act. Changes to other related laws include:

- exemptions to grid fees for energy-intensive firms should be done away with completely

-

a clearinghouse should review all remaining exemptions regularly

-

Germany should launch a minimum carbon price; the Greens specifically point to the UK example

Overall, the Greens estimate that their proposals would lower a four-person household’s annual power bill by 35 euros.

It is easy to see where other parties will criticize this position paper. For instance, the Greens argue that the electricity tax (unrelated to the renewable surcharge) should not be reduced to lower retail rates as that tax revenue would simply have to come from some other source. But German industry says basically the same thing about energy-intensive exemptions: if you raise power prices so high that firms cannot be profitable, you end up losing jobs. The trick, as always, will be finding that magic middle ground.

The Greens are not completely out of the race for the upcoming parliamentary elections, but it will be tough. Current polls indicate that the Social Democrats and the Greens would not be able to form a coalition if the elections were held today, so the Greens are most likely to be able to form a government with the CDU. Though it has never happened before at the federal level, such a coalition seems like the logical next step in Germany’s political landscape. The main problem is that a CDU/Green coalition would have too little support in the Bundesrat, so a grand coalition of the CDU and the SPD seems likely at this point.

In all likelihood, the Greens will therefore have a hard time getting their proposals adopted.